By Sean Cantwell & Pete Keenan

In the classic novel A Tale of Two Cities, Dickens describes the era of pre and post-revolutionary France as both an age of wisdom and foolishness. Building and growing a successful business obviously requires wise decisions to overshadow bad ones along the way. This is especially true for how companies manage external capital on a path to exit.

There is more to capital efficiency than meets the eye. Large equity rounds that look ripe for reckless spending are justified when that capital can be deployed to fuel responsible customer-focused growth. Venture capital firms often take a reductive view of capital efficient businesses as those that take limited amounts of external funding — usually less than $10-15 million.

However, funding alone does not determine capital efficiency: it’s how those dollars are deployed and the growth, recurring revenue, and valuation that they generate.

The most capital efficient company isn’t always the company that has raised the least capital. For example, if company A has raised $3 million with $10 million in recurring revenue, everyone would say that they are remarkably capital efficient. But if company B has raised $25 million with $85 million in recurring revenue, few would point to their capital efficiency though they are, in fact, slightly more capital efficient.

As check sizes have grown over the last decade, VC and growth equity firms need to reconsider what it means to be capital efficient. Let’s dig a little deeper and examine three very different companies that have all gone public. Veeva, Domo, and Chewy.com.

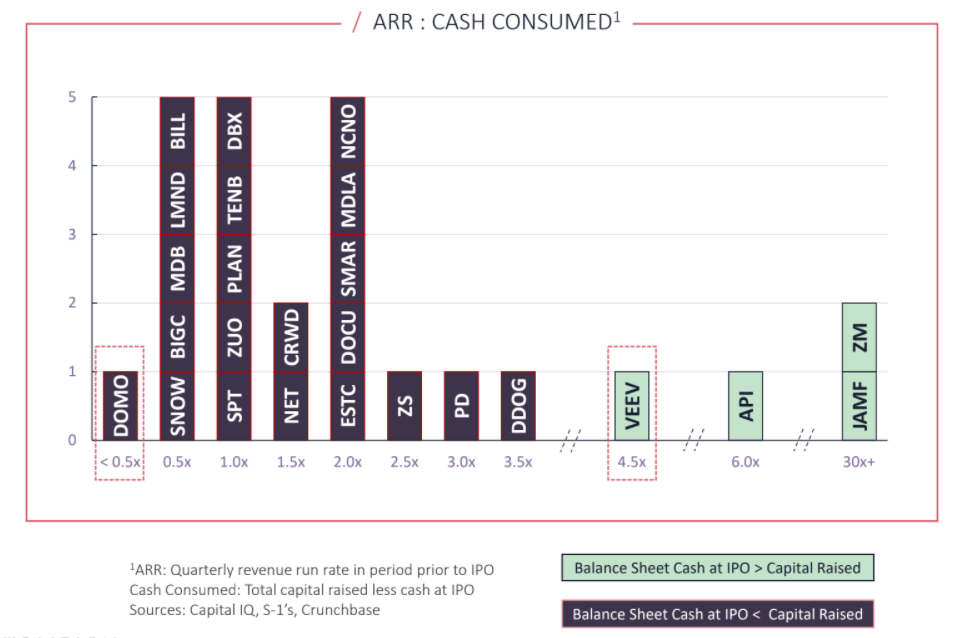

The ARR Efficiency Ratio

To figure out the valuation of companies in between rounds of financing, many SaaS investors look at annual recurring revenue (ARR). This is where the ARR Efficiency Ratio comes in. The ARR Efficiency Ratio takes Cash Burned over, where Cash Burned equals Capital Raised – Cash on Hand – Founder Liquidity:

ARR

÷

Cash Burned

Think of this as a real-time snapshot of capital efficiency rather than the final picture. The reason Cashed Burned is used is because many companies still have significant amounts of capital on their balance sheets even as they head towards IPO. For instance, Slack raised $1.39 billion of outside capital but had $849 million of unspent cash at IPO.

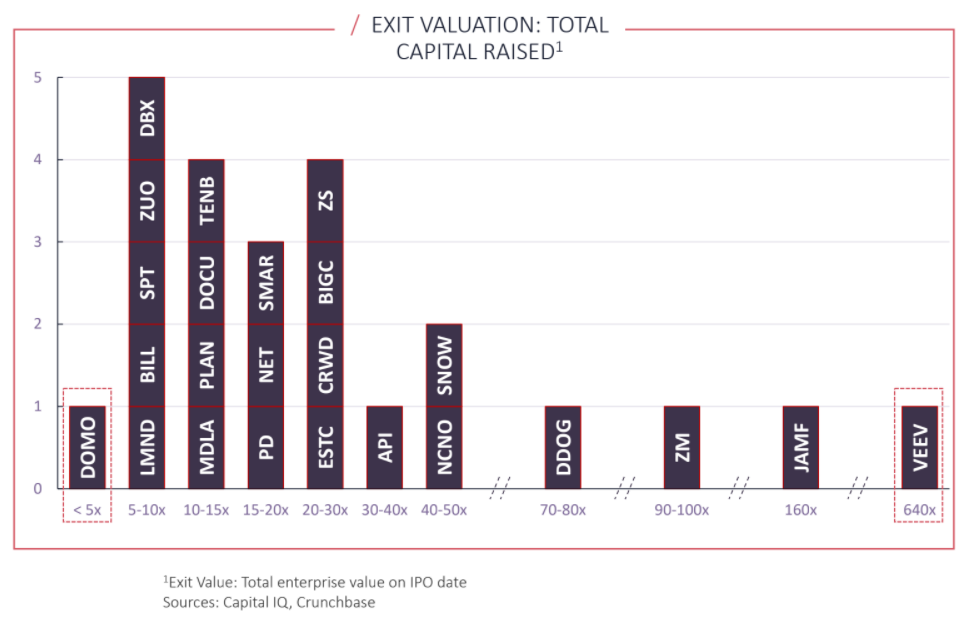

The Venture Capital Efficiency Ratio (VCER)

While metrics via recurring revenue or profit are an intermediate way to benchmark capital efficiency, the ultimate arbiter of capital efficiency is exit price. Defined simply, capital efficiency is the least amount of invested capital to drive the maximum equity return. This can be expressed in a simple ratio:

Exit Valuation

÷

Total Capital Raised

This is what some call the Venture Capital Efficiency Ratio. We use total capital raised in place of cash burned because it can often be difficult to determine cash burn, though it is a more accurate arbiter. The higher this ratio, the more capital efficient the business. Ratios below 1 would be considered complete capital efficiency failures, 1-5 would be solidly capital efficient, 5-10 very capital efficient, and 10+ extremely capital efficient.

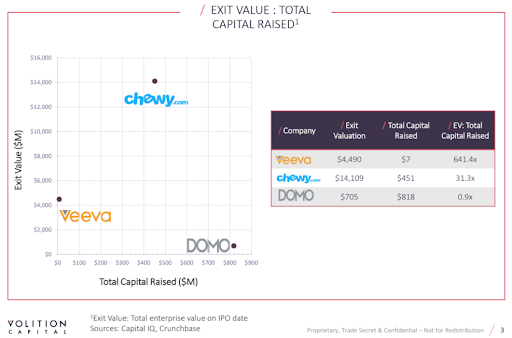

The ultimate example of a capital efficient company is Veeva, which raised $7 million and went public at a valuation of $4.49 billion according to Crunchbase for a ratio of 641.4 (pretty much off the scale). On the other extreme, we have Domo which raised over $818 million but went public at a valuation of $705 million according to Crunchbase, for a ratio of .9.

Was Chewy.com Capital Efficient?

Though companies like Veeva are ideal, sometimes raising larger rounds in pursuit of responsible growth is the best option. Consider our former portfolio company, Chewy.com, which, though not a SaaS company, had a very interesting trajectory.

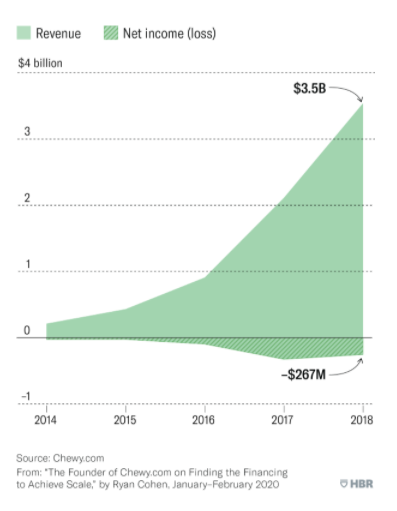

Volition Capital invested $15 million as the first investor in Chewy.com back in 2013. Over roughly the next four years, Chewy.com went on to raise $451 million dollars in funding according to Crunchbase, an amount that for many could fuel rapid and irresponsible cash burn.

While dilution is certainly a concern for any initial investor during follow-up funding, we also knew that founder Ryan Cohen and the team at Chewy understood their market well. While Chewy’s customer acquisition costs (CAC) are certainly high and have been going up over time ($68 for each new customer in 2017 to $148 in 2019), Chewy has been able to develop remarkable customer loyalty by placing emphasis on the customer experience and relationship. In fact, purchases by existing customers represent 90% of its revenue, which eclipsed $4.8 billion in 2019.

As Chewy.com founder Ryan Cohen explained in an Op-ed in CNBC in 2019:

Between 2014 and 2018, the company burned only $134 million in free cash flow while growing revenue from $200 million to over $3.5 billion and spending approximately $750 million on marketing

That means that despite raising huge amounts of capital, Chewy.com deployed that capital remarkably efficiently to grow revenue. By the time Chewy.com IPOed in 2019, it was valued at over $14 billion. With only $451 million in total capital raised, this makes its VCER 31.3, or more than 30x more capital efficient than Domo. Though Veeva’s 641.4 VCER is still remarkably high, it is important to note that Chewy.com had not burned through all of the capital it had raised by the time it IPOed. It also operates in a non-SaaS environment where raising smaller rounds in pursuit of growth is more difficult to do.

How to Raise Money and Be Capital Efficient at the Same Time

A lot of companies raise money because they can, not because they should. As investors, we don’t want companies that take venture dollars to immediately invest in branded Patagonia jackets and nitro cold brew machines in the office. We want them to keep a bootstrapped, metric-driven mentality, where they treat pennies like manhole covers and only spend in the pursuit of judicious growth.

Capital efficiency isn’t about hoarding money, but war chests can be a good idea sometimes especially if you are anticipating an economic meltdown. If you think you can raise at a 7x multiple today but a 1x multiple tomorrow, then you probably should raise today.

The goal should be to maximize equity value while minimizing dilution, but if you are in the position where increasing dilution a little could raise valuation a lot, this is actually a more capital efficient move.

We’ve certainly had moments where we’ve thought follow-up rounds of financing were not justified, but we encourage all of our portfolio companies to ask the following questions to determine if raising more capital is right for them:

- Have you grown your valuation enough to justify this round?

- Have you identified the uses of capital for incremental raise?

- Do you think the markets will bear this move?

- What are your tactics on how you spend?

Ultimately, we want founders to retain control by growing responsibly rather than chasing sloppy growth where they dilute their shares, forfeit control, and spend imprudently. A capital efficient company doesn’t have to have only raised a small amount of external funding, but it does have to be balanced. Chase growth on one hand, but spend judiciously on the other. As I’ve argued in my post comparing the SaaS Rule of 40 to the story of the tortoise and the hair, the best entrepreneurs will balance their business needs with the market forces around them, finishing the race at the pace that’s best for them.

Sign up for our mailing list to get Volition Viewpoints in your inbox:

Meet the Authors:

SEAN CANTWELL

Managing Partner

Sean Cantwell is a managing partner and member of the founding team at Volition Capital. He focuses primarily on companies in the Software and Tech-Enabled Services sectors.

Connect with Sean:

Pete Keenan

Sr. Accountant

Pete joined the Volition Capital team in the Fall of 2019 to support the investment team with fund administration, financial modeling, and legal document review.

Connect with Pete: